Background on Project

Devon Waugh, an Information Science graduate student, approached me about being her master’s paper/project advisor in summer 2018. Devon has a background in special education and an interest in digital accessibility that she wanted to apply to her research.

She posed this research question: How accessible is the UNC Libraries website’s navigation page to databases for users with visual impairments?

Our focus for the usability test was on the information retrieval and research habits of UNC undergraduate and graduate students who used some form of assistive technology like screen magnification or a screen reader.

The planned tasks moved the participants from the library’s E-Research by Discipline page into a Frequently Used database then back to the E-Research by Discipline page and into another subject-specific database under the Environmental Sciences category. The research topic participants were asked to use was the effect of pesticides on honey bees, which was considered broad enough to not require outside knowledge for completing the tasks. The goal within each database was to locate a relevant article and access or download the PDF version of the article.

Preparing for User Testing

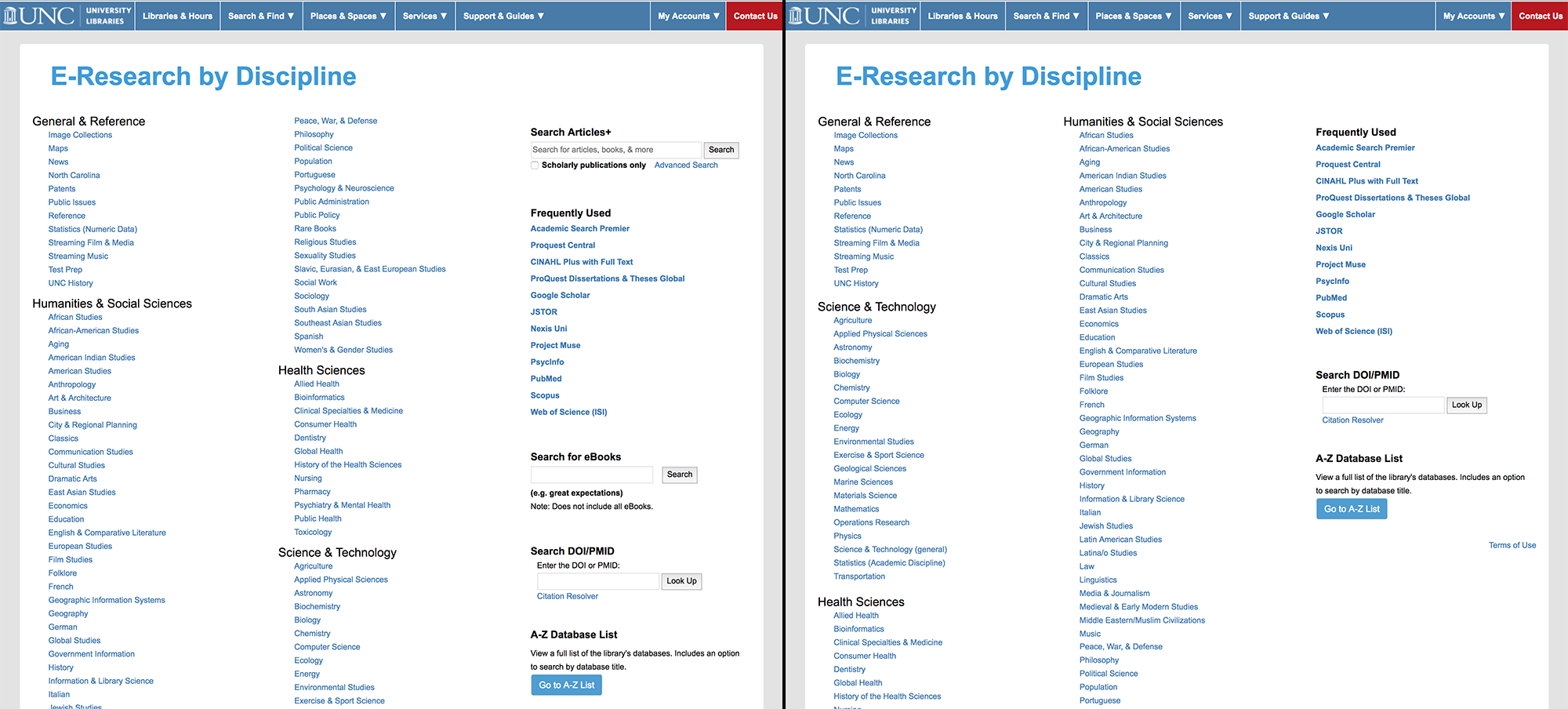

Prior to sitting down with our participants, we made changes to the E-Research by Discipline page to prepare for the in-person usability testing. This included rearranging the order of subjects on the page so the longest list, Humanities & Social Sciences, are now in one single column. This layout allows users to skim through the 4 main categories then locate a specific discipline within their chosen category rather than assuming they will read the page left to right like a print document.

To improve the semantic layout of the page, headings were arranged to be properly nested with one H1 on the page followed by H2s and H3s for subsections. HTML

Other changes to the page included simplifying the third column by removing 2 of the 3 search boxes. A label was added to the DOI/PMID resolver that was left on the page. This resolver was used more than the other 2 searches previously on the page combined.

The purpose of these changes was to improve the usability and accessibility of the E-Research by Discipline page before having users sit down to complete the usability test tasks. Our goal was to make the page as accessible as possible and remove barriers that might impede the participants’ during testing.

And they paid off:

Honestly it’s one of the better pages I’ve seen on a website, it’s pretty easy to get around. The titles help me, it’s like reading a menu, I struggle with reading menus but this is easy to read.

Findings

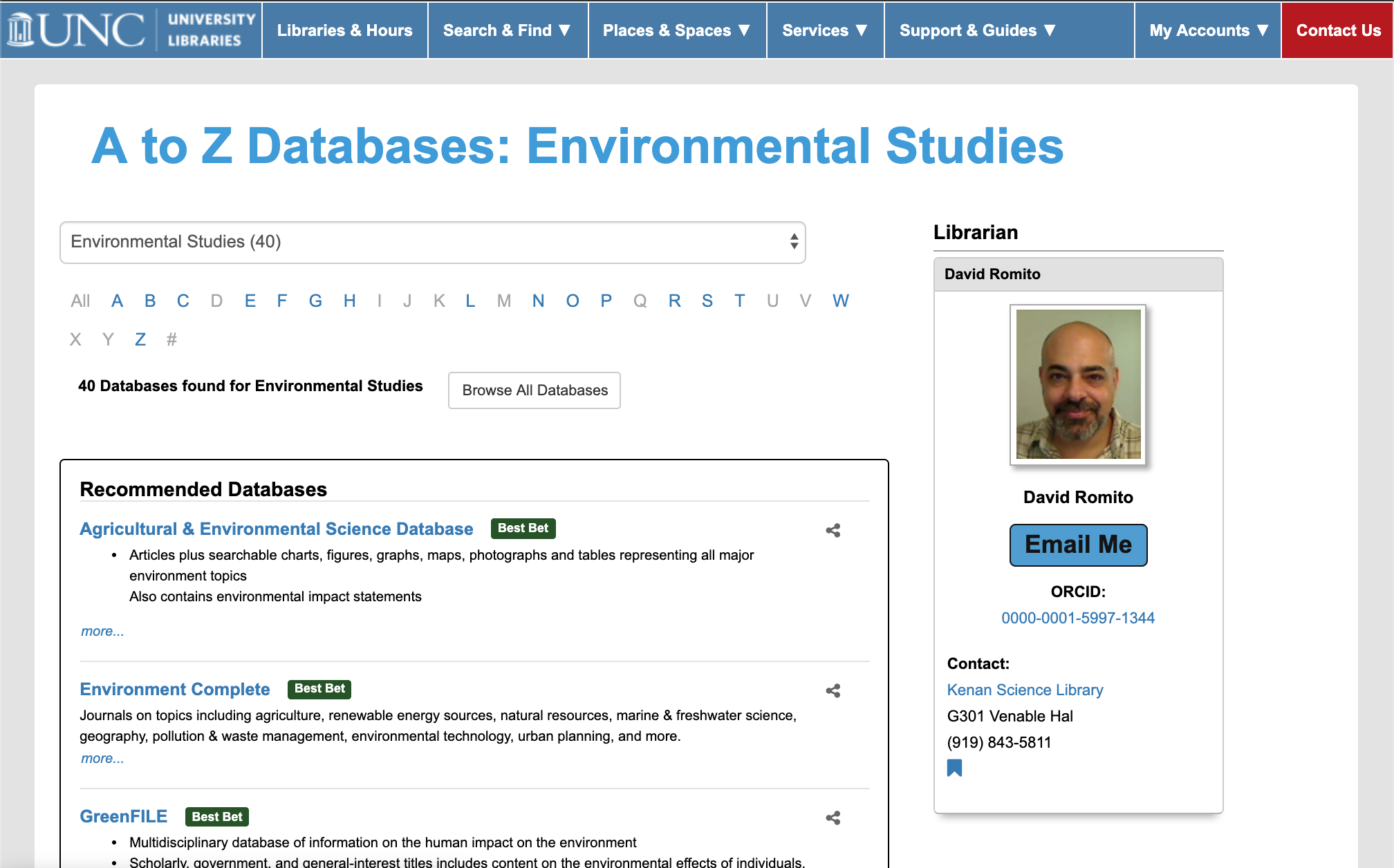

As successful as our changes to the E-Research by Discipline page were, our participants did discover issues during testing. Some issues, like on the A-Z Database subject pages, are within our ability to address. Others, like labels for PDF downloads in different databases, are not.

Changes to A-Z Database Pages

All three participants selected one of the “Best Bet” databases as a good place to start. But each had different uncertainties about the meaning of best bet or “Start Here,” which is what the Recommended Databases used to be called at the top of the page (see image above).

One participant states:

They have the few at the top that are supposedly best bets, not that I know how they determine what goes there and in the alphabetic.

Because of their feedback, we changed Start Here to Recommended Databases to be clearer about the purpose of the first set of databases on each subject page.

Academic Search Premier (Ebsco)

Participants were directed to use Academic Search Premier, one of the library’s Frequently Used databases that covers a broad array of subject areas. One out of the three participants told us they had never used this database.

The major roadblock we saw for the participants in this database was identifying a search result with a PDF. One participant selected the first result, but couldn’t find a PDF download option. They returned to the results and found the link for “PDF Full Text” from the results page. After completing the task, they stated:

Sometimes when I’m legally blind, I don’t know if it just wasn’t there or if I’m just not seeing it. Maybe it was there. Sometimes I’ll search for so long.

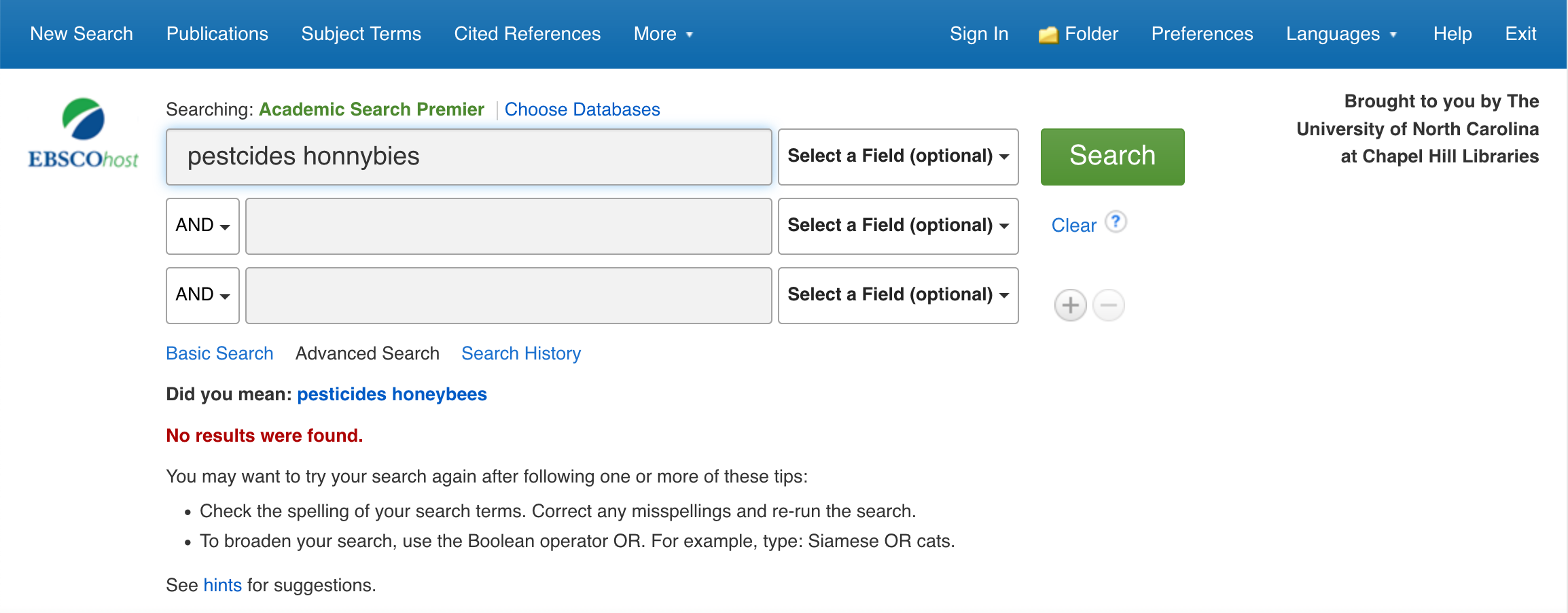

One participant ran into issues with navigating the search results page via screen reader because they had to get past the advanced search options before getting to the main content of the page even if there were no results based on their search terms.

Related to this, the participants frequently had issues with spelling. One participant even used Google’s autocomplete to find the correct spelling for their search before copying and pasting it into the database. This leaves an opening for better autocomplete functionality in the database. Along with easier navigation options for getting around the search bars, participants needed more guidance or alerts for spelling and search term suggestions. This is especially crucial if they mistype and end up with zero results because databases can vary in their responses for spelling support.

Subject-Specific Database

In the final task, participants were asked to select a subject-specific database of their choosing from the Environmental Sciences subject page. Two participants chose Agricultural and Environmental Science Collection from ProQuest. The third participant selected the Environment Complete database from Ebsco.

Agricultural and Environmental Science Collection (ProQuest)

The differences from the first database created confusion such as slight changes in language (e.g. PDF Full Text versus Full Text PDF) and the location of search bars or results.

The simplified basic search page tripped up the two participants who used this database. They both felt they were missing key information using the database. One participant put it as:

Once I was able to find stuff, it became a lot easier. I think they’re there, I just wasn’t seeing them. I guess it was just kinda hard. I didn’t know where to click.

The other participant ran into an issue accessing the PDF version of a relevant article using a screen reader. They successfully located the PDF and opened it within the browser, but because the PDF was in a frame, the screen reader was unable to access the text. It took the combined effort of the participant and the investigator to understand what was happening and how to download the PDF to open it outside of the browser window in Adobe Acrobat. This issue was the most challenging and concerning we saw throughout the usability testing.

Environment Complete (Ebsco)

This database turned out to be a list of article citations exclusively, instead of offering any attached PDFs. The participant who selected this database did not complete the task of finding a relevant article for this reason. They reviewed 20 out of 35 search results and ended up frustrated by only being able to access “abstract reference and notes” instead of the full text.

The investigator pointed out our Find @ UNC button to access one of the results in a different database, but the few results the participant tried ended up not being available through our online holdings, creating further frustration.

While not specifically an accessibility issue, this shows the importance of considering our users expectations and experiences when making resources available to them. Consider what a novice user would think of a citation-only database and how the library can set up a user like this for success before they access the resource.

Limitations of Study and Next Steps

This study has the usual limitations of a usability test. Mainly, the most significant limitation was the challenge of recruiting and especially, focusing on a particular user group. The study required interested survey respondents to have a visual impairment to participate in the follow-up usability test. In retrospect, this screening question needed to be more clearly defined to focus on what assistive technology (screen readers, screen magnification, high contrast, etc.) the user needs to interact with a computer or mobile device. Even within this definition, there will be a variety of types of visual impairments that could be solely addressed instead of looking at a mix of impairments and technologies.

All three participants mentioned searching for known items rather than browsing for articles as the tasks asked them to do. Further research could focus on this approach to research or even conduct user interviews to try and get a clearer picture of how users with visual impairments research in higher education.

Overall, the databases we subscribe to and have students using need to be held to the same standards as our own websites and tools. One participant summed up this experience by saying:

The E-Research by Discipline page itself is fine, the tricky thing is the databases with significant variations. Finding a database part is all very nice, then the issue is ‘Now what?’ that’s not the E-Research by Discipline’s fault, but whoever created the database.

The full version of Devon’s master’s paper is available in the Carolina Digital Repository.